All over Europe we are working to develop next generation free and fair societies that can combine global competitiveness with social cohesion and sustainability. Across local governments and communities, schools, education institutions, the healthcare sector, businesses and many other sectors we are working to solve these, often wicked, problems and create new opportunities. And increasingly we work together in order to inspire each other and pool resources, share knowledge and not least strengthen Europe’s position and influence in the world.

These are often complex challenges that call for everything we have got in terms of creativity, knowledge and innovative capabilities – areas where design-driven and human centred methods are recognized for their ability to bring people together in order to create and innovate.

“Design is what links creativity and innovation.

It shapes ideas to become practical and attractive propositions for users or customers.

Design may be described as creativity deployed to a specific end”

– The Cox Review[1]

However, the process of these methods doesn’t immediately go well with the processes of EU projects. Hence, to help make the most of the many projects we develop each year, we have designed a model specifically for the development of EU innovation projects that merges the typical administrative flow of EU projects with the methodological processes of design-driven innovation.

The framework is inspired by works by Design for Europe, IDEO, Nesta, OECD, The British Design Council and many other interesting organisations, as well as a number of scholars and practitioners, including Stappers and Sanders, David and Tom Kelley, Tim Brown, Neumeier, et.al. The framework is not intended to function as a set procedure, but in the spirit of design-driven innovation, more as an inspiration and a reminder of the different aspects and the flow of a project capable of combining creativity with thorough analysis and to deliver results within the scope of EU projects.

The mindsets of creativity and innovation

Before diving into frameworks, methods and clever things to do, let’s get off on the right foot. Perhaps the most important thing about working with creativity and design-driven innovation is that it is basically an optimistic approach to life, confident that new, better things are possible and that you, I and we can make them happen. We can make a difference, solve problems and improve our lives by unleashing our creativity, analytical capability, our knowledge and experience, and trusting our instincts and imagine what is not yet there, but could become a brilliant solution. Then act, fail, try again, make changes, try again and make it come true.

“Creative confidence is the notion that you have big ideas,

and that you have the ability to act on them.”

David Kelley[2]

This optimistic, persistent and experimental approach is the common thread in an innovative approach driven by a creative mindset with an equally strong ability to analyse and to see patterns and correlations. Without this kind of optimism and belief in once own creative capabilities, the framework is merely an empty shell. Perhaps you may want to take a closer look at the mindsets of creativity and innovation here: MINDSET OF CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION before you move on.

Designing a framework for EU innovation projects

The framework suggested here is created by merging two well-known representations of the design-driven innovation process, having more or less the same flow, but emphasizing different aspects of the process.

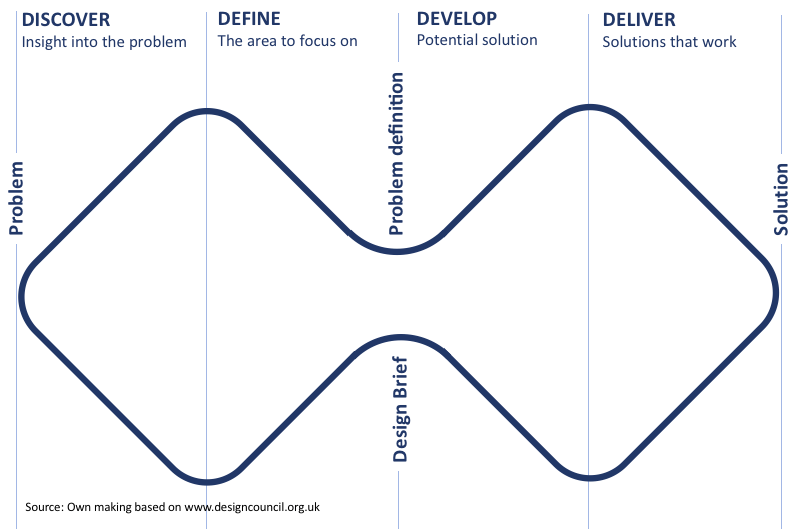

The first model is the Double Diamond model by The British Design Council – see figure 1. The model organises the innovation process into two main phases each with “divergent” and “convergent” stages forming a 4-stage model consisting of Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver.

In the first diamond we explore the problem, look for inspiration, define the project and formulate a design brief for the project, including problem definition, expected outcome and deliverables, resources, budget, etc.

In the second diamond the defined problem is further explored in details and a potential solution is developed, prototyped, tested and developed into a final solution that is implemented. (Design Council[3]).

Figure 1: Double diamond

This straight forward model, fits pretty neatly with the typical two stage process of EU projects like ERASMUS+ from the first initial exploration of the challenge and the writing of a project proposal (corresponding to the design brief), to the second implementation phase, where solutions are developed, implemented and disseminated. As such the Double Diamond works well as an overall framework for the organising and planning of EU education projects.

However, dive into the creative and generative processes and research methodology and it becomes clear, that we need to dig a bit deeper to get a useful model. A key aspect and purpose of EU projects is to innovate and develop solutions together through collaboration, and knowledge sharing – often with a strong emphasis on user-involvement. Hence an EU project model should be designed to accommodate these innovations and collaborative activities, and made to rest on a methodological foundation, capable of fostering creativity and innovation.

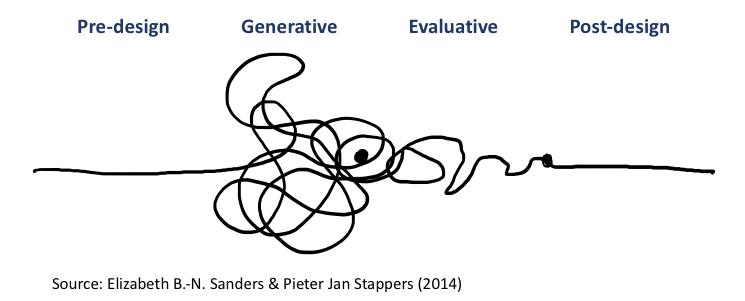

Hence, in order to make room for these core processes of creativity and innovation in our framework, the double diamond structure has been combined with “structure challenging” insights from Sanders and Stappers (2014)[4] see figure 2.

Figure 2. Phases along a timeline of the design process

Here the development process is illustrated as a squiggly line while still progressing through four phases along a timeline: Pre-design, generative, evaluative and post-design. The first dot in the graphics indicates the definition of the design challenge (design brief) and the second dot represents the finished outcome of the process. Let’s take a look at the insights we can gain from the Sanders and Stappers model.

Firstly, the model extends the process with the pre-design processes that here translates into a pre-project process, in order to include the crucial fuzzy process prior to the project where the ideas for the project are conceived, and the problems framed.

Secondly, the model also extends the process into the equally important continuous work that should follow after the project in a post-project phase to ensure the sustainability of the project, and to look at how people actually experience the outcome (product, service). Ultimately the post-project research ends up being a new pre-design phase leading to continuous development and sustainability.

Thirdly, the squiggly line defining the generative phase, but also characteristic for the evaluative phase makes it clear, that there is much more to creativity and innovation than sleek project management and evaluation processes. Creativity and innovation are based on iterative and non-linear acts of making and trying things out, seeking new insights and ask questions not answered yet, to let solutions emerge. It might be a cliché, but creativity and innovation do include learning by doing, trial and error, inspiration and elements of chance.

Hence, Sanders and Stappers’ discussion of the design process, illustrated with their squiggly line ads depth to the sleeker Double Diamond model. And with both models being laid out along a time line, build around similar concepts of divergent and generative vs. convergent and evaluative thinking, it seems obvious to merge the two frameworks into a model that allows room for creativity and innovative action, and at the same time reflects the necessity of working with application schemes, coordination and a fixed timeframe.

Taking a look at the two models together, the generative part of the squiggly line corresponds with the explorative nature of the divergent phases in the double diamond, and the evaluative part corresponds with the convergent phases of the diamond framework. In that way the squiggly line offers insights into the nature of the processes going on in each of the diamonds.

Within the context of many EU innovation projects including ERASMUS+ KA2 and 3, we normally run through two cycles of generative/divergent and convergent/evaluative processes. The first one during the design of the project, resulting in the project proposal. The second one during the implementation of the project, hopefully resulting in a useful solution to the challenge we defined in our project proposal. This fits neatly with the systematic of the double diamond and with the design brief / project proposal linking the two diamonds.

However, as Sanders and Stappers stress, the project starts a lot earlier with the fuzzy front end, where the project idea is conceived. An important part of the creative process is the point where inspiration and imagination meet in ideas for new opportunities and solutions on how we might deal with a challenge. From my experience this early part of the projects is a lot more generative and defining for the projects than indicated by the lines drawn by Sanders and Stappers, suggesting a more “squiggly” front end.

In the other end of the process we saw Sanders and Stappers stressing the importance of the post-design research, thereby hitting a sore spot in many international projects. While the best projects manage the difficult but rewarding art of creating a working international collaboration on innovation, fewer manage to sustain the project and continue to build on its results. While everything seems just about done at this time of the project, this might just be the beginning of several circles of innovation and value creation. It is a part of our project that deserves a lot more attention, in order to strengthen the level of innovation and sustainability of our projects.

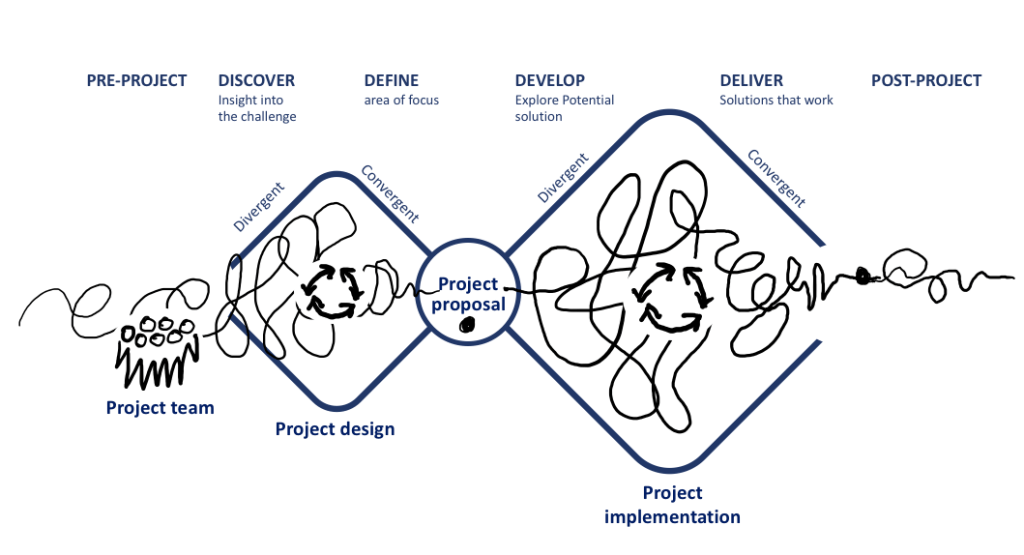

By merging the double diamond and the squiggly line, we now have a framework consisting of 4 primary phases with six key processes throughout an innovation project as illustrated in figure 3. With the main part of the work and time spent during the typically 2-4 years of implementation, we redesigned the diamond to a less elegant, but more illustrative version, with a smaller project development diamond and a bigger implementation diamond. All in all, we then get the project framework illustrated in figure 3. Let’s take a closer look at the details of the structure.

The pre-project is the fuzzy period before initiating the project process where we reflect over our daily praxis, get inspired or make unusual connections in order to see new possibilities, or where we may be just plain puzzled by a challenge that we need to solve. Even though this is very early on, this is also a quite defining period for a project, as we tend to choose our approach rather early – and maybe too early! There is therefore a good reason to stop and seek for alternative angles beyond the immediate subject matter. Including potential partners at this very early stage, if possible, is not only a good way to challenge your own perspective, but also a great way to start the collaboration and lay the foundation for a good consortium. Forming the project team early on allows us to tap into everyone`s skills and networks at an early stage, and test the expediency of a possible team in terms of competences, resources, expectations and – not least – personal chemistry. This is especially important in the case of international projects, where establishing a group capable of collaborating and thriving across cultures for the best part of 3-4 years, can be particularly challenging.

Figure 3 Framework for Innovation projects

The first diamond is where the project is designed. The process is kicked off with the initial discovery phase laying the ground for the project in a divergent and generative process, where the project team explores the problem, conducts pre-research, gather new insights in order to expand their approach and to understand and empathize with users. Trying to apply alternative perspectives to be able to see new things and allow for fresh ideas and new understandings to emerge.

This is done through preliminary research, gathering inspiration, looking into new approaches or technologies and seeking inspiration – perhaps from other areas or industries. The result should be a rich resource of inspiration, insights and knowledge with enough depth to make it possible for the team to define the problem and outline the project during the following convergent process, where we evaluate the challenge, define the problems, design the project and summarize it all in the project proposal.

Define: The second phase of the first diamond is a convergent process where insights, findings, and pre-research from the first phase is reviewed, analyzed, synthesized and interpreted in order to make sense of all the findings. All the ideas and possibilities are evaluated. What matters most? What are the constraints of the project? What do we believe is feasible within our timeframe? What fits with the needs of the organization and the actors involved. When working with EU projects these considerations have to be matched with the call for project proposals, including priorities, expected scope, goals and deliverables.

This leads us to the writing of the project proposal – the final outcome of the first diamond. This should outline and substantiate the background for the projects and the scope, selected approach (theoretical basis) and goals of the project as well as anticipated activities, organisation, staffing, timing, budget, expected outcome and specific deliverables and dissemination of the results, as well as the sustainability of the project after it is terminated. If one is responding to a call for a project, the application should reflect the priorities, scope and expected outcome as well as deliverables specified in the call, and other requirements and criteria.

The second diamond is where the action starts, after our proposal has been approved and funded, we pick up where we left. Rather than being a simple and sleek process, it means continuing the development work, but this time with the resources and time to make things happen and to go into details. Ideas have to be brought into life. Solutions, products and services will be developed, tested, altered and finally delivered or implemented throughout the “Develop” and “Delivery” phases.

DEVELOP: The third phase of the double diamond is the second divergent process of researching and exploring the challenge in depths, gather insight and empathize with users in order to be able to develop actual solutions to the projects task, outlined in the project brief and/or project application. Now is the time where the ideas and concepts imagined in the previous stages are put to the test and developed into prototypes, tested and iterated in a process of trial and error – a process that is at the core of human creativity and our ability to move beyond the known.

This is the part of the project where you need to muster confidence in your own creativity and innovative spirit. A process that might span everything from logical and deductive “solving” of problems, to the more open-ended, open-minded, and iterative process[5] of exploration and “working through” the problems in order to find valuable solutions as described by Marty Neumeier[6]

This includes non-logical processes or intuition as argued by OECD in their take on Core Skills for public sector innovation[7]. The more complex and wicked the problem is, with no “definitive definition” possible, the more we have to rely on testing and intuition. While intuitions might be “…an uncomfortable topic for many disciplines because of its apparent lack of seriousness, it is in actuality a critical skill honed by experience and central to many designers’ practice. In the context of strategy, intuition requires full investment of time and thought, so as to acquire a sense about how things fit together.” “Also testing is dependent on intuition to the extent that it requires experience to know how to test ideas efficiently and productively.” [8]

Non-logical processes, experimentations, playfulness and relying on the tacit knowledge of your intuition are at the core of creativity and creative confidence. Creativity is by nature wild and untamed and should not be hampered by a manage-and-control focused mindset. That would only obstruct the process and cause a mediocre outcome, as this will rule out random inspiration, wild ideas and playful “what if” experiments. The key is to act and to make things outside the comfort zone of what you think you know.

DELIVERY

The last part of the development work is a convergent process where we synthesize and conclude on the experiments and knowledge gathered in the development works. This is the time for making choices and deciding what matters most, what solutions to go with and to turn prototypes into functioning solutions that are taken through the last circles of testing and finalized. As discussed earlier this is not a linear process, but might very well involve several loops between the divergent and convergent processes of the develop and delivery phases.

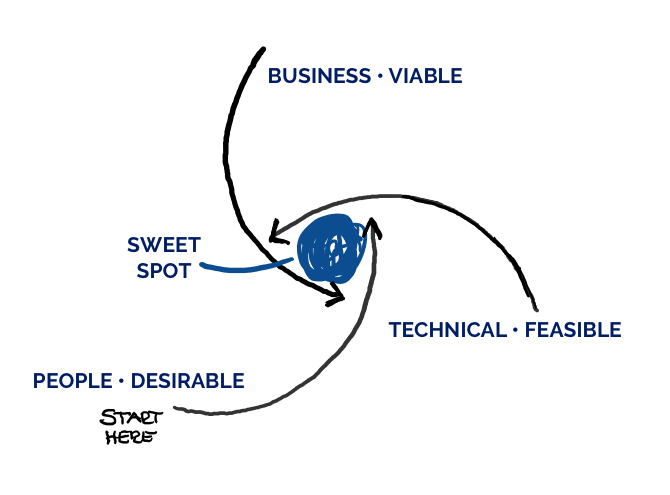

Balancing constraints. This convergent process of making choices and deciding which solution to go with, involves balancing conflicting interests and aspects and working with constraints.

This can be seen as balancing three sets of constraints or factors. Firstly, being human centered, the point of departure is empathizing with users and understanding their hopes, fears and needs and uncover what’s desirable and what solutions would probably appeal to the users. Secondly, this has to be balanced with technical, organisational, legal, time, etc. constraints, in order to determine what is actually feasible to implement, and thirdly, what is viable businesswise / financially. Together these three factors have to be balanced to hit the sweet spot, where what is desirable for people, what we believe is feasible to do and what could be a viable and sustainable solution for our problem come together and form valuable and sustainable solutions.

Figure 2

Disseminate. When you feel that this is it, the product or service is launched. In many European projects “launching” also means dissemination or in other words sharing your findings and results in order to maximize the European value and outreach of the project. This is not only a question of publishing your results, hosting a conference and setting up a website. Rather than a “communicative” approach, a much more interactive and collaborative approach is required. Hence, a good consortium embedded in a relevant professional network, collaborating to put the innovations of the project into good use is crucial for leveraging the value of the project.

Finally, there is the post-project, where we have the opportunity to evaluate and realize the long-term effects and continue the evolution and development of the original solution. The obvious challenge is that this part of the project is not funded. Thus, unless the implementation is designed in a way that embeds the solution in a new practice across the consortium, this is often a part that is neglected. It is of course easier said than done. However, part of the purpose of our South Danish network for education is to facilitate that our alumni projects can stay in touch, continue their collaboration and perhaps develop further innovation activities together

[1] Design Council, Design methods for developing services. https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/DesignCouncil_Design%20methods%20for%20developing%20services.pdf

[2] http://www.designkit.org/mindsets/3

[3] https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/design-process-what-double-diamond

[4] Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers (2014) Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning, CoDesign, 10:1, 5-14,

[5] Brown, Tim, Change by design: how design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation, HarperCollins Publishers, New York 2009, p.17

[6] https://www.martyneumeier.com/knowing-making-doing

[7] OECD, Core skills for public sector innovation, A beta model of skills to promote and enable innovation in public sector organisations, 2017

[8] Opcit p. 50