In the latter years, climate policies have come to the fore of the Commission’s attention. Recognising that the climate crisis demands a common multilateral response, involving rethinking and reconstruction of several parts of the European industry and energy supply, the Commission presented in 2020 the nascent idea of the Green Competences Framework, which formed part of the European Green Deal. Until then, sustainability did not have its own framework but was woven into the existing eight key competencies for life-long learning.

In 2022, the European sustainability competence framework was finally published by the Joint Research Centre (JRC), as it was introduced together with the Commission’s proposal for a Council recommendation on learning for environmental sustainability. The general idea behind the GreenComp framework is to define a common ground for the term ‘sustainability’ within education.

“Our aim is to provide a shared competence framework on sustainability at

European level as a common basis to guide both educators and learners.”

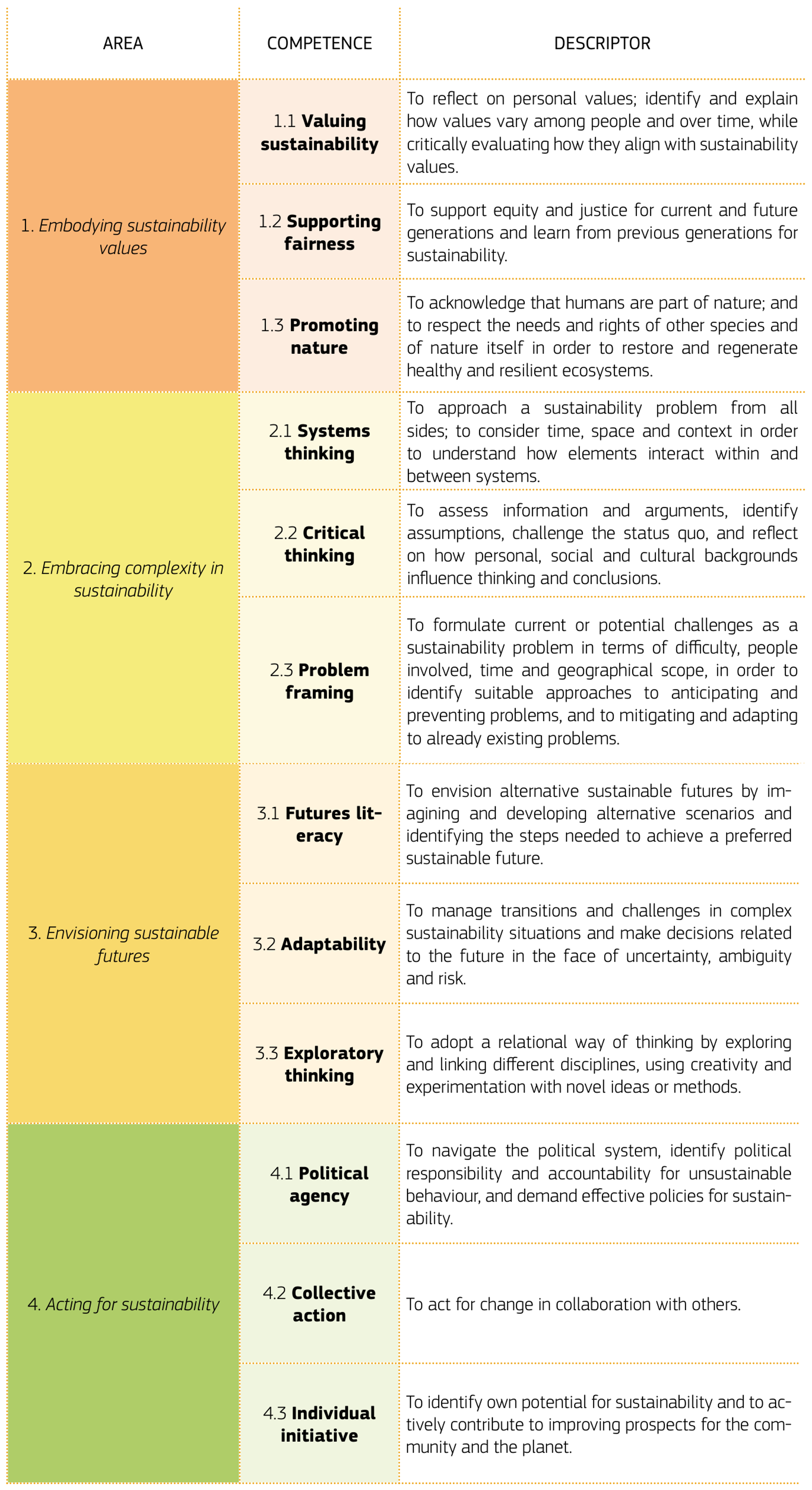

To do so, the framework has been divided into four competence areas containing three competencies each (see box below). An extensive elaboration of these competencies can be found in the full report.

The competencies do not reveal a hierarchy since each of them is highly interrelated. Instead, they simply offer different entries to the policy report, while also adding a sense of structure to it. In general, the framework has three easily identifiable purposes. Firstly, it seeks to establish a terminology, which may be used as a common reference point for educators and policymakers; secondly, it attempts to complement and strengthen the existing national material within different fields of education and, thirdly, it tries to cue educational policymakers to prioritise the added value of sustainability in teaching. On top of these observations, it is an objective to engage young graduates from an early age into working constructively with the green transition.

Throughout the report, definitions of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in relation to each sustainable competence have been developed. By doing so, the authors have attempted to make the recommendations more tangible. For instance, skills related to the ‘political agency’ green competence is translated into “the ability to identify relevant social, political and economic stakeholders in one’s own community and region to address a sustainability problem.” This feature provides a level of measurement to the Green Competencies, which can be used in the assessment of a person or entity’s ‘sustainable competencies.’ A term that otherwise may seem rather abstract and vague.

The usefulness of it may however be questioned since the framework does not address specific proficiency levels or vocational sectors. Instead, the report is thought of as a conceptual and generic model, which needs adaptation to the specific context. Co-writer of the report, Ulrike Pisiotis, has indeed confirmed that the framework is devised as a living document, serving the function of a common reference point for the creation of further subject-specific guidelines.

Consequently, the framework has multiple uses, making it applicable to education and training policies, curricula review, teaching material and resources, non-formal education, and assessments as suggested before, within a wide range of vocational areas.

Looking ahead, it shall be interesting to see, how national educational institutions will manage to incorporate the framework into their local educational curricula and teaching material and whether the Commission will initiate specialised implementation recommendations for different vocational fields.